Estimated reading time: 13 minutes.

April/2018 – The Sigma 100-400mm f/5-6.3 DG OS HSM is a super-telephoto zoom lens capable of fitting 6.3º of a diagonal field of view on a 135-format full-frame; made to shoot subjects from afar. A specification not long ago dedicated only to top of the line lenses like Canon’s EF L and Nikon’s AF-S, at f/4.5-5.6 aperture, this Sigma does it at about a half-stop less at f/5-6.3; thus cheaper to manufacture and easier to use. At just US$799 (launch price) we get a genuine super-telephoto zoom for sports, social events, landscapes and wildlife; but here meant for the amateur market with a light and easy to use operation. With a plastic body, smaller glass pieces and simplified controls, could the Sigma 100-400DG be the best low-cost telephoto lens? Let’s find out.

At 18.2 x 8.7cm at 100mm of 1160gr of plastics, glass, rubbers and some metal parts, the Sigma’s 100-400mm f/5-6.3 size immediately gets our attention; it’s indeed much smaller than its f/4.5-5.6 peers from the professional market. It’s the exact same idea from other super-zoom lenses from the Contemporary lineup like the 150-600mm, that’s almost half the size of the f/4 600mm primes; or the ultra-portable 18-300mm f/3.5-6.3 DC; all made with the amateur photographer in mind. Such portability comes from the advanced TSC usage (thermally stable composite), a plastic material more robust than polycarbonate but as resilient as aluminum; made for the everyday, always-with-you use. So the 100-400DG feels robust and free of misalignments, and it’s also very smooth to the touch; it certainly feels premium despite the lower US$800 price on the entry-level market.

In your hands its usability is practical and simple, without any bells and whittles; meant to always be with you. While the 100-400mm focal length makes it long at about 24mm when extended at 400mm, or up to 30cm long with the included-in-the-box lens hood, its balance feels fantastic; especially when mounted on full-frame cameras. Here shown with the Canon EOS 5DS, its ergonomics are perfect: a large camera at the rear, held by the right hand; and the (relatively) light zoom lens at the front, supported by the left hand; all in balance. This stability is mandatory for precision when working with telephoto distances, and the overall combo is so light that it doesn’t even require a tripod collar; it all should be mounted directly on the camera.

At the front the zoom operation is smooth with a generous rubberized ring. The front position is a good decision for a longer telephoto lens, forcing your arms to be extended during use – thus balancing the camera and stabilizing the frame. From 100mm to 400mm the zoom movement is done with not much force at about 90º, faster to shoot action despite Sigma’s inclusion of a secondary movement to adjust zooming. The included-in-the-box lens hood doubles as a push/pull area to manually extend the lens without turning the zoom ring, the same as Canon’s classic EF 100-400mm (not Mark II), for even faster framing. So it’s interesting to see both ideas implemented on this Contemporary DG lens, and you decide what works best for your photography needs.

At the center barrel the manual focusing ring brings another surprise: smooth, precise, recessed; a pleasure to use. The Global Vision Contemporary zoom-lens lineup is all over the place with its focusing rings: both 17-70mm and 18-300mm feature weird rings that move together with the internal HSM motor and doesn’t allow for a full time manual operation; and the 150-600mm super-zoom sports a thin rear focusing ring, bad for its precision and lackluster grip. But this 100-400mm DG ring is virtually perfect with about 2.5cm (2cm rubberized) and, at the same time its recessed in the lens barrel, harder to touch by accident, it’s nice to use, with plenty of grip. It turns 180º from infinity to 1.6m (minimum focusing distance), at a 1:3.8 maximum magnification; good enough for some macrofotography, added the precision of a large distance window. Again, it is better than Canon’s classic 100-400L that uses a center focusing ring but a rear window that’s very hard to see.

Inside Sigma uses its HSM auto-focusing motor that’s almost standard on every Global Vision lens; not the fastest, not the slowest. It’s usability is smooth, precise and reliable, and tested on the EOS 6D Mark II is accuracy rating surpassed 80%; reasonable for a super-telephoto lens, specially coming from Sigma. It’s “reliable” because at about 234mm the maximum aperture reaches f/6.3, above the f/5.6 limit from most entry-level EOS cameras. But tested on the EOS T3i, EOS M and EOS SL2 – the “worst” cameras I have on my kit – it all worked flawlessly. The side switches also make it easy to adjust between AF, MO and MF modes, although I didn’t get the MO (manual override) addition; it already supports the full-time manual operation at AF. But overall it’s all straight forward to use: point the camera at your subject; start the AF; and the lens focuses.

On the other hand the 100-400DG focusing speed is not the best, and you can loose some unexpected moments. The same “focusing cycle” we saw on the 135mm f/1.8 happens with this zoom: instead of confirming focus instantly, the lens follows a slower seeking > approximation > interval > confirmation; at about a full 1-second. It’s very different from Canon’s USM that locks on your subject as soon as you press the camera’s button, and the Sigma may screw the photographer’s timing. Despite the focusing limiter switch offering two shorter positions from 1.6m to 6m (near shots like red-carpet events) and 6m to infinity (field sports), the focusing speed doesn’t get faster. While the HSM motor is fast enough to keep up with moving subjects like the weekend’s cyclist at Avenida Paulista (examples using the EOS 5DS SERVO mode), we are stuck with the same old recommendation for Sigma: they’re getting better AF, but still far from Canon’s USM.

“Cyclist” with the EOS 5DS + Sigma 100-400mm f/5-6.3 DG OS HSM at f//6.7 1/1000 ISO1600 @ 400mm.

Also inside Sigma offers its optical stabilizer (OS) module made to “hold” your composition in place; avoiding blurred shots. A nearly mandatory feature on longer focal lengths, the idea is to make due without a tripod while using slower shutter speeds, compensating for the hands movement directly on the optical groups. And it works quite well: while the OS won’t freeze your subject’s motion (it’s not useful to shoot people), it’s welcomed for landscape and product photography. Also although nothing is declared about its technology and compensation ratio (in stops), the 100-400mm OS is surprising: it is at least 3-stops of compensation from 100mm (1/6s) to 400mm (1/20s), greatly enhancing the “image quality” under low-light (with reduced ISO speeds). And despite the same weird operation from the 150-600mm, compensating only the exposure, not the viewfinder, it works well for most shots; simply keep the OS on to get the best results.

But for video this stabilizer is not the best. As the compensation happens mostly during the shot, the somewhat smoothness that should come from a OS module is not noticed during Live View; and that’s a problem. Here shown together with Canon’s EF 100mm f/2.8 L IS Macro USM the difference is obvious: the Sigma 100-400mm “jumps” from side-to-side, giving a very jittery recording. It’s the same issue I noticed on the 150-600mm, 18-300mm, 17-70mm and the 17-50mm; they can’t compare to Canon’s IS. Although some of these lenses are compatible with Sigma’s USB Dock, providing different modes for the OS module including one for continuous compensation, it still doesn’t make much difference. So I can’t recommend the Sigma 100-400DG for videos, as it feels the OS doesn’t work, despite its good performance for photos.

Finally at the front the 100-400DG accepts ø67mm filters thanks to its modest f/5-6.3 aperture. They fix on a robust plastic thread over the first optical element that itself is held in place with external Phillips screws; easier to replace in case of damage. This thread fits inside the LH770-04 lens hood that’s included-in-the-box, and one of the most robust I’ve ever used. As it serves the double function of a push/pull zoom with a groove to fit your finger, and its plastic is tough and well finished; smoother to the touch. At the rear the 100-400mm uses a rubber gasket to seal it against dust and water, although nothing is declared about a proper weather sealing scheme. The last lens element is also recessed to support Sigma’s 1.4X and 2X converters, also compatible with Canon’s EF 2X III extender; but with manual-focus operation only. The 100-400mm fits the amateur market for its smaller aperture, simplified operation and great feature set for the price. But only its images can seal the deal. Does a low-cost super-telephoto zoom is any good in taking pictures? Let’s see.

“Sunset” at f//5.6 1/750 ISO100 @ 400mm.

DISCLAIMER: The aperture data might be wrong on some shots. The EXIF states f/5.6 even at 400mm despite the lens minimum f/6.3. Consider the maximum f/6.3 for those shots.

With an overly complicated optical formula of 21 (!) elements in 15 groups, four (!) high-performance low-dispersion glasses (SLD), anti-reflection treatments and a 9-blade rounded aperture, once again what Sigma delivers on the Global Vision lineup is insane; almost the most complex optics ever on vlog do zack! Behind only Canon’s EF 70-200mm f/2.8 L II IS USM and ahead of larger telephoto lenses like Sigma’s own 150-600mm, Canon’s EF 200mm f/2 L IS USM prime; and even its 100-400L peer, this 100-400DG is clearly at the top of the intermediary market; at least at this focal range. The image quality is good: the resolution is great on most of the frame, especially at 100mm, great for product and portrait photography. Its sharpness drops at 400mm, noticeable only on large-format prints. But the overall aberration control is excellent, with almost zero lateral chromatic aberration and no axial CA. The only issues are the severe vignetting at f/8-f/11 and the overall geometry, distorting straight lines. All-in-all the images are great.

“Sea” at f//5.6 1/250 ISO100 @ 361mm.

Wide open the Sigma 100-400mm resolution is good, better at 100mm than at 400mm. A pretty standard behavior for a zoom lens, it’s hard to complain about the last decade’s lens performance; the resolution is impeccable on almost 90% of the frame. From the center to the edges we do notice a slight drop in details near the corners, better delivered by larger aperture primes. However tested with Canon’s entry-level EOS 6D Mark II at 26MP, it’s easier to “loose” sharpness due to the difficulties in shooting telephoto images (atmospheric distortion; short depth of field; focusing precision) than for lens anomalies. Landscape shots are acceptable for reasonable prints up to A1 size (not A0), more than enough for the “weekend photographer” that might post the images on Instagram. So it’s easy to recommend it for both the super-telephoto and the low-cost markets.

Crop 100%, interesting sharpness for a super-telephoto zoom.

Crop 100%, sharp details on the frame’s edge, even wide open.

Crop 100%, plenty of wide open details.

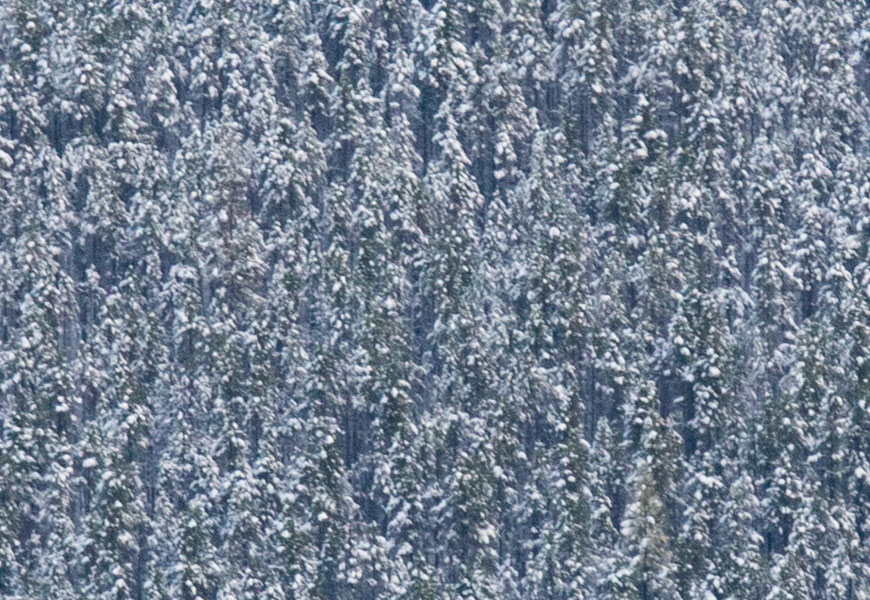

Stopping down shows some enhancing on the frame’s corners, filling the final 10% of the shot with details; better for higher quality images. Between f/7.1 and f/11 the image clarity looks better from the center of the optical formula, also enhancing contrast and sharpness; near perfect on the 6D Mark II’s 26MP. This performance is also great to work with the smaller APS-C format, plagued with lesser lenses from first parties like Canon’s EF-S 55-250mm, despite this generation’s “crop” cameras featuring higher pixel density than most full-frames sensors. So it’s possible to recommend a EOS T7i + 100-400DG kit for landscape and wildlife photographers at the 160-640mm focal length, keeping nearly the same flexibility of much larger (not to mention expensive) kits. It’s a new paradigm to the entry-level market, now more accessible and capable than ever.

Crop 100%, impressive resolution for a 135-format zoom lens.

Crop 100%, nice prints with plenty of details on a budget.

Crop 100%, atmospheric distortion is always a challenge for maximum sharpness at this focal length.

The chromatic aberrations are another surprise from the 21 elements optical formula, extremely well controlled due to the TSC strength in keeping everything perfectly aligned. The highlight goes to the lateral aberrations: very fine lines are seen only on high contrast edges with green and purple halos, easy to fix in post. It wasn’t long ago when Canon solved CA on the top EF 70-200mm f/2.8 L IS II USM zoom using one fluorite and five (05!) ultra-low dispersion (UD) pieces; fixing aberrations on a US$2000 lens! But Sigma delivers the same performance on a much cheaper lens, thanks to its high performance glass and low-cost manufacturing. Also the axial chromatic aberration is invisible on the telephoto formula and, despite some rare blooming issues (light leaks on high contrast areas), mostly visible at the closest focusing distance, this zoom performance would be nearly as good as some primes. It’s a pleasure to use on the super-telephoto market now at a low cost.

Crop 100%, nearly invisible lateral chromatic aberration; job well done, Sigma!

Crop 100%, also minimum axial aberrations on the out-of-focus image plane.

Crop 100%, once again the invisible lateral chromatic aberration from Sigma’s zoom lens.

What doesn’t work and is an unforgivable issue strong enough to not keep the 100-400DG on my kit is the vignetting; impossible to get right on such a low-cost design. We can’t bend the laws of physics: the modest f/5-6.3 spec is great for reducing its size, weight and price, making is very easy to use just like the 150-600DG and Canon’s own EF-S55-250. But that’s exactly what takes the most out of the image quality and, no matter the aperture setting, the frame’s edges are too dark from 100mm to 400mm; hard to fix even in post. Yes, it’s a relatively easy fix on Adobe’s Camera Raw or Lightroom, or even in-camera depending on its software; magically brightening the frame’s edges. But we don’t need trained eyes to see the image quality dropping with visible noise and less saturation. So that’s a big disclaimer: this lens is NOT suitable for professional images.

The same can be said about its geometric distortion, visible on compositions that might display straight lines; like the horizon on landscapes. So many glass elements on a variable aperture zoom makes composition lines “drop” onto the center frame giving the impression of a pined cushion; bad from 100mm to 400mm. It’s stronger than Canon’s 100-400L and the EF-S55250, but standard on Sigma’s longer zooms (150-600DG and 18-300DC showcase similar behavior). Actually most low-cost and mirrorless brands are leaving optical geometric distortions to be fixed electronically, opting for either cheaper lenses or better corner details. But it’s far from advisable for high precision shots given the slight drop in sharpness with all the pixels pushing in post. The first party professional lenses obviously deliver better performance on either its primes or zoom telephotos.

Finally the colors and bokeh are fair on this 21 elements zoom lens. Here tested on Canon’s EOS 6D Mark II signature science color, the photo album looks fantastic: vibrant, saturate, neutral and easy do handle; despite once again feeling a bit behind the 100-400L series I used a few years ago. Yellow, green and blue tones are strong under direct sunlight, demanding as little as +10 and +5 adjustments on both vibrance and saturation sliders to bleed the colors for high impact. Orange, red and pink tones are even stronger for great looking sunsets and natural portraits. And the out-of-focus bits looks smooth only when we’re working near the minimum focusing distance (1.6m). If you’re far from your subject and the depth of field isn’t shallow enough the bokeh tend to get confusing, considering the smaller aperture. So carefully plan your background on these kind of shots; it might not look as good as the larger aperture lenses, nor we’re expecting such.

“Yellow” at f//8 1/320 ISO100 @ 400mm.

“Bizão” at f//6.3 1/640 ISO2000 @ 400mm; bad bokeh on the background.

The Sigma 100-400mm f/5-6.3 DG OS HSM is one of the most cohesive products on the Contemporary Global Vision lineup. The smaller aperture is perfect to make the lens smaller, something I’ve complaining about the Art lenses since the 50mm f/1.4. It’s build is surprisingly light and robust with the good usage of the TSC. Both focusing and zoom rings are smooth with a silent AF motor that’s not the fastest, and the image stabilizer is good for up-to 3-stops. It’s easy to be seduced by the f/4.5-5.6 alternatives on the professional market but they can quickly become a burden; only very well paid photographer should carry the large lenses offered from first parties. But the Sigma optical formula is surprisingly good with 21 elements in 15 groups, despite also being cohesive: its images are high-res; the aberrations are under control; and it can easily output for the web or smaller prints. So once again this Sigma can be a market’s favorite on a budget, despite being harder to be recommended for professionals. This won’t take the place of larger f/4.5-5.6 zooms, but the images can be as good. Just add it to your kit and nice shooting!