Estimated reading time: 10 minutes.

April/2018 – The 135mm f/1.8 DG HSM is, for now, Sigma’s longest Art prime lens. Introduced in 2017 it arrives after the manufacturer completed its f/1.4 lineup, with high-performance lenses from 20mm to 105mm, from the 24mm to the 35mm to the 50mm to the 85mm; and now with a smaller f/1.8 aperture at the limits of the focal range. A popular focal length for portraits and landscapes, the 135mm are offered on virtually every system be it on large aperture primes (like Canon’s EF 135mm f/2); or inside a zoom (70-200mm f/4L). The shorter depth of field from the longer focal length is excellent to keep some distance from the photographer and the subject, giving human figures pleasing flat noses and ears; and invisible geometric distortions (good for landscapes). But Sigma once again takes the focal length to the next level opting for a genuine “short telephoto” formula, just like it did on the 85mm Art DG: large low-curvature lenses enhancing the frame resolution; distinct from first parties double-Gauss lenses. Is it any good? Let’s find out!

At 9.2 x 11.5cm of 1130 grams of plastics, metals, glass and rubbers, once again what Sigma did on the 135mm f/1.8 Art DG HSM makes no f•cking sense: big and heavy to justify the telephoto optical formula. I know it sounds annoying so soon on a review, and I understand size and weight are subjective. But we must question Sigma’s decisions: aren’t these lenses getting way too big? Be it the 50mm f/1.4 or the 85mm f/1.4, both enormous and the biggest among its peers, and you really must love Sigma & notice visible advantages on its images to consider carrying this 135mm around. On the other hand what it gets big it gets robust, and once again we see Sigma’s TSC (thermally stable composite) used at its best: this lens is mostly plastic but extremely well made, as the material features the same metallic properties of aluminium, despite weighing 30% less (accordingly to Sigma); and it cost less to produce, perfect for cheaper lenses. So there’s little to complain about it’s built, with no cracks or major misalignments, ready for duty.

In your hands the lens is big and heavy, despite the reasonably good ergonomics; this 135mm is better balanced than even the 85mm f/1.4 Art. That lens was larger than this 135mm, despite the shorter focal length; Sigma really pushed the boundaries on that 85mm at f/1.4. But the 135mm keeps the sober Art series design and finishing introduced in 2012, with a metal fishing near the lens mount followed by a rubberized surface at around 3cm, made to rest your fingers. The manual focusing ring is not as large as the 85mm Art and sports about 0.5cm in height with 5.1cm in length (4.2cm covered with rubber). And it spins 180º from infinity to the minimum focusing distance of 87cm, long and precise, simple to use with an advanced “full time manual” operation; even with the switch set to auto, the photographer may still use this ring to further compensate the focused distance. Finally a side panel fits AF/MF controls and a limiter with three options: full; from 1.5m to infinity; and 1.5m do minimum; with a shorter range the motor can lock focus at twice the speed.

Inside Sigma employs its latest HSM motor, thinner and with a higher torque, introduced on the exotic 50-100mm f/1.8 zoom; silent, smooth and pretty fast; at least on that lens. On the 135mm the giant optical formula asked for a special “floating elements” focusing group, rear mounted and independent from the rest of the lenses; made for higher focus precision, not for speed. Let’s be blunt: both 85mm Art and 50-100mm DC and 150-600mm DG set new benchmarks for Sigma’s AF speed, and they’re all amazing for the the aperture (85mm), format (50-100mm) and focal length (150-600mm). But the 135mm DG is clearly aimed at precision, slower than most. Here tested on Canon’s EOS 5DS, the lens takes about a full second to focus, with a weird AF cycle: seek > approximation > and then focusing – it’s not seek&lock as Canon’s USM. It’s slower than the EF 135mm f/2L USM, an action photographer’s favorite; and slower than any EF 70-200mm USM zoom; despite not particularly dreadful. Most importantly on SERVO mode it didn’t have any issues following Avenida Paulista’s cyclists, and it’s precise; less than 20% of shots came out of focus.

“WonderWoman” with the EOS 5DS + Sigma 135mm f/1.8 DG HSM at f/2 1/2000 ISO320.

100% crop, acerto de foco SERVO quase perfeita, with thepenas uma foto fora de foco. (clique para ver maior)

Finally without a built-in stabilizer or any special features, the Sigma 135mm f/1.8 DG HSM ends on a plastic ø82mm filter thread at the front, smaller than the ø86mm 85mm f/1.4 Art, thus incompatible; despite being cheaper and easier to purchase (the ø82mm are the new ø77mm). The included-in-the-box lens hood is a simple tube that fixes by friction at the front, and adds about 9cm to the lens; it’s gigantic and feels like a proper mini-telephoto lens in your hands. The first and last glass elements are fluorine coated and easier to clean, in case you get dirt or grease from usage. And the mount features a rubber gasket made to seal it agains water and dust, although nothing is declared about a proper weather sealing scheme. Last but not least the final lens element is fixed and not recessed in the mount, this incompatible with extenders (Canon’s 135mm f/2 can be transformed into a 270mm f/4 with a 2X converter). What Sigma did on the Art DG HSM is truly a mechanical monstrosity, made to justify the exotic optical formula, less practical than its peers. Maybe a critique on its optical performance can justify the purchase of another big Art lens.

“Canyon” at f/1.8 1/250 ISO800; todas as fotos with the Canon EOS 5DS.

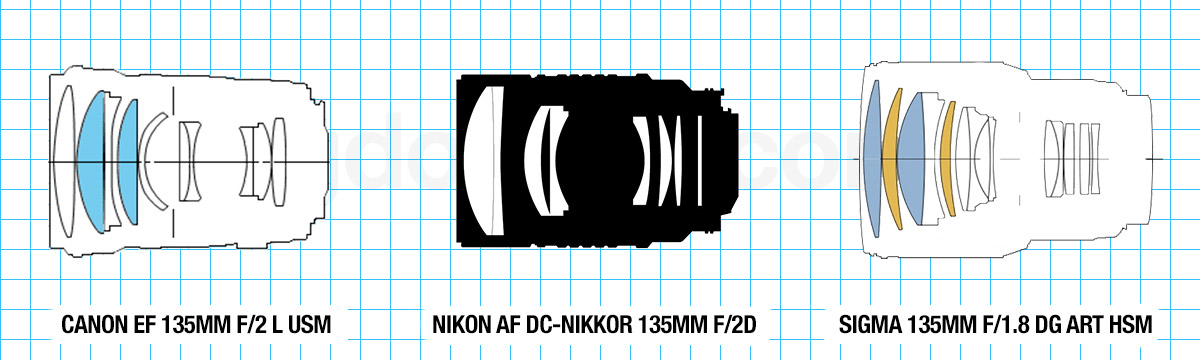

With a very complex 13 elements in 10 groups optical formula, two low-dispersion glasses (SLD) and two exotic FLD glasses (that Sigma declares the same properties as natural fluorite; absent from the 85mm Art); all with a 9-blade rounded aperture and chemical anti-reflection treatments; once again what Sigma delivers on the Art series is… curious. The 135mm focal length is very popular for portraits and, with no major updates from first parties (Canon and Nikon designs are almost two decades old – each!), Sigma didn’t have to try hard to seduce the photography market; begging for new lenses from the millennial generation. Fix some aberrations here and there; enhance corner resolution; and most less-informed photographers would be drooling over it on the internet. But we simply can’t bend the laws of physics, and once again Sigma drops the ball with a low-cost lens. This 135DG is based on a miniature “telephoto” formula, longer and with better resolution, yes; but not with the same image characteristics as Canon’s and Nikon’s double-Gauss 135mm; and that’s a problem. The results: lackluster photos with minimum separation between background and foregrounds; and flatter out-of-focus bokeh, without the Gaussian natural look.

“Canyon II” at f/1.8 1/250 ISO800.

A quick look at the optical formula illustrate the Sigma’s 135mm Art image qualities. The larger-than-life glasses keep the field curvature low, with absolute resolution from edge-to-edge; great for precision photographs of landscapes and products. But to photograph people, other optical characteristics would be better. The spherical distortion of a double-Gauss formula is much better at separating the foreground from the background, due to its field curvature with enhanced geometry front and back; giving some depth to the out-of-focus bit (larger at the front, smaller at the back). The vignetting around the edges from the Gaussian formula also enhance the color saturation and smooths the edges of highlights, also for a much more “organic” bokeh. But that doesn’t happen on neither the Sigma 85mm or 135mm. So lower depth of field portraits look like artificial defocus on both SIDES of your subject (not front/back), and it looks bad. That’s the purchasing decision: the Sigma for excellent edge-to-edge resolution; or the double-Gauss lenses?

That’s not the say the Sigma 135DG images look awful. Wide open and given the flat curvature from the large aperture and high performance glasses, the f/1.8 photos are probably the sharpest we’ve seen from a prime lens. Wide open landscapes deliver better details and less aberrations than Canon’s EF 70-200mm f/2.8 L II IS USM – a top-of-the-line zoom costing US$1999! It’s bizarre to see the results from the EOS 5DS, the highest resolution 135-format camera on the market, with perfect window frame details at f/1.8 at night, at 50MP; paving the way for new types of photography. For astrophotographers it’s now possible to register cosmic details for a fraction of the cost. High precision studio portraits with pre-made backgrounds can be done with zero chromatic aberrations (that are chaotic on vintage lenses). And for myself who own an EF 200mm f/2 L IS USM just to shoot high-resolution landscapes at f/8, this Sigma lens is a game-changer; we’ve never seen so much details at 135mm and now at f/1.8; all for a low-cost from a mini-telephoto prime.

100% crop, the unbelievable wide open resolution, worthy of a telephoto prime.

100% crop, impressive sharpness from the EOS 5DS 50MP monster.

100% crop, large prints from the large aperture prime.

What doesn’t work is the out-of-focus quality; incredibly flat without significant gradient changes between planes. On a double-Gauss formula the image’s characteristics are obvious: concave “fisheyes” on specular highlights on the corners of the frame, given the lenses spherical geometry; less defocus from elements closer to the focal plane, and larger as farther they get; and vibrant edge tones given the frame vignetting. But on a telephoto formula, like the one used on this Sigma, with larger diameter glasses with less curvature, there’s little to see on the bokeh; the geometry looks the same front and back. When we exaggerate such effect shooting a tridimensional object at a 4/3 perspective, it looks like lateral defocus: both left and right sides look the same, harder to understand what’s at the front (larger) and what is the back (smaller). Subjects looks like cardboard cutouts in front of a static background, and that’s an easy purchasing decision: just like the Sigma Art 85mm, the 135mm is excellent in its resolution and details, but it’s not the best for portraits.

“Welt” at f/1.8 1/250 ISO2000; if it wasn’t from the lettering, we would hardly notice what’s at the front or the back.

“Cyclist II” at f/2 1/2000 ISO1600; the background is blurred but the subject feels like a cutout pasted on the image.

Stopping down have a minimum effect on the overall image resolution; virtually perfect from f/1.8. What do gets better is the axial chromatic aberration on out-of-focus details visible on highlights, and the positive compensation of the vignetting, invisible as soon as f/2.8 (!). Secondary axial aberrations simply doesn’t exist on this Sigma, a giant leap forward the Canon 135mm L. Remember those colored lines around high contrast edges? Yeah, they’re not here. It’s an excellent performance for precision shots straight from the camera and very useful for amateur astrophotography, that can be done on a high resolution lens costing a fraction of the cost; with an exotic large aperture. And for studio photography this Sigma sets new standards for image quality: perfect wide-open f/1.8 shots, great for product or beauty photographs.

100% crop, visible details from the 5DS frame edge.

100% crop, impeccable sharpness from a prime lens.

Finally the colors are Sigma’s 135mm f/1.8 DG HSM last surprise: relatively saturated and natural despite the low contrast; much more vibrant than the 85mm f/1.4 Art. Thanks to its two FLD glasses with performance similar to fluorite (and no chromatic aberrations), the colors are “happy” tested on a Canon EOS camera. Blue, yellow and green tones are natural straight from the camera, without software enhancing. Shadows reflect the time of the day giving an atmosphere to your images, with deep brown tones at noon; orange near the sunset; and blueish by the end of the evening. Portraits look natural with pink tones on caucasian skin, and firmer hues on darker subjects; although both less saturated than Canon’s 135L. But easy to fix: any white balance slider or tone gradient adjustment can make Sigma’s photos look similar. Also with excellent flaring resistance and perfect chromatic aberrations, the Art series are closer to first parties lenses.

“Flowers” at f/1.8 1/2000 ISO100; nice colors under sun light.

The 135mm f/1.8 DG HSM is, like any Sigma Global Vision Art lens, a pleasure to review and work with. They’re big, chunky and with questionable ergonomics; those in favor of a mirrorless market may get confused with Sigma’s decisions. But in your hands the experience feels premium like no other low-cost brand, and their passion in building beautiful things is noticeable. It’s also easy to use as we expect from a +US$1000 lens, with a perfect manual focusing ring, precise and smooth to the touch; and a welcomed floating elements focusing group, great for high image quality despite it’s slower operation. The optical formula hides the high performance on a budget, with a strictly telephoto design; but too flat for pleasing portraits. So while Sigma does set new standards for corner resolution and aberrations at f/1.8, never before delivered by other brand, it looks weird for shallower depth of field shots; maybe the most used setting for this focal length. So as usual it’s a careful recommendation for your kit. It’s worth for what it is – and that’s a telephoto lens – but it’s not the best lens ever. For portraits, keep your Canon or Nikon 135mm lenses, and nice shooting!